How Not To Do a Hackathon

I’m a strong believer in learning by doing. I don’t think it’s necessarily the best way to learn because you invariably learn inefficiently, repeating well known mistakes and suboptimal practices. If you have a mentor throughout the learning process they can lead you away from bad habits and, crucially, explain why they’re bad in the first place.

But there are plus points to learning by doing. Firstly, you can’t argue with the results. It’s not a theoretical endeavour and if you manage to build a bookcase in two weeks, you can be fairly certain you’ve learnt a thing or two about carpentry. Additionally though, even though there is pain in learning the hard way that the bad habits are bad, there is no greater lesson learned than that which you learn yourself. Put bluntly, you’re more likely to remember to continuously save your work after you’ve lost six hours of content to a crashed application rather than someone simply advising you to, “Save your work frequently.”

The first Hackathon I ever did wasn’t an organised event but rather a weekend hanging out with a few other software developer friends. It was great fun and felt promising but ultimately, it has to be regarded as a failure: there was no end product. For those who are good taking lessons learned from others, here are my biggest suggestions to keep in mind when doing a Hackathon.

What’s a Hackathon?

I suspect that anyone reading this blog is fully aware of what a Hackathon is, but for completeness I’ll describe it briefly. A small team of software developers – anywhere from two to about a dozen – free up their calendar for a few days so they can work solidly on a fun coding project. Nothing to do with the popular “media” definition of hacking.

What I failed at

My friends and I spent an enjoyable, sunny day in a pub by the Thames river in London discussing ideas. We were similar people, we had all worked for the same multinational corporation in the past but had since diverged into different industries and technologies. We were looking for a good idea that would inspire all of us for a weekend; something we’d all want to use. In the end we decided upon a multiplayer football manager game, not a totally unforeseeable conclusion considering how much football we all played and watched.

The result after the end of the weekend was at best a promising start. One, however, that never caught hold. I was the first to admit a few months later that I wouldn’t be submitting any new code to our group’s source control.

Suggestion 1: MVP. EM! VEE! PEEEEEEE!

This bit of advice works well for startups too. Know what your MVP is: minimum viable product. If you can’t see the parcel tape holding the shoddy bits of code intact, you worked on it too hard and too long. The MVP should be small. It should be so basic it’s embarrassing. It should have mockups in place of genuine UIs if you can get away with it. There is nothing more disheartening than setting yourself a small goal for a weekend of sacrifice only to miss it by a colossal margin because you tried to make something too functional and/or polished.

The goal of a Hackathon is not to have a finished product ready to be launched immediately to the public. It’s to have a promising prototype, something that tests the water. If it doesn’t feel right, you and your teammates can say, “We gave it a go but it doesn’t seem as useful or revolutionary as we hoped it might be.” But if your prototype holds some promise, that first v0.1 provides inspiration and motivation to keep going. The Hackathon pace likely cannot and should not be maintained, but if it can provide a spark, go and get it more kindling!

Suggestion 2: Interfaces over Technology

For a Hackathon you’re doing greenfield development i.e. writing brand new code, not maintaining existing code. You also won’t have the overhead of planning or bugtracking software (though some Trello boards can be very useful). Dividing work into coding tasks and assigning those tasks is part of the fun of the Hackathon process. However distinct the tasks are though, your code has to integrate with at least one other developer’s code for it to be any use.

Often, Hackathons are times to try out something new whether that’s a new framework or a new language altogether. Technology shouldn’t be the focus of the discussion though – any team member should be able to write their code in whatever technology they wish. The crucial part to focus on is the interface. Not necessarily a programming level interface (as used in Java, C# etc.) or concrete web API, but more a high-level understanding of how one developer’s Go code is going to be used by another developer’s F# code.

Even if you’re all programming in Python, there are frameworks, third party libraries and conventions that, perhaps not all agree to or are familiar with. Thinking clearly up front about how each developer’s contributions will interact with the others will save time in the long run. If contemplating code interactions appears too complicated to consider as a first step, I suspect Suggestion 1 has already been violated.

A second (solo) attempt

In the case of our Football Manager Hackathon, we got both the above elements wrong. At the end of the weekend we had disparate bits and pieces to show but nothing end-to-end. Our tech stack was just as disparate with code written in Python for the Django web framework, a Dojo web frontend and Objective-C for the iPhone implementation. The large initial remit made working on interfacing new code clumsy and iterative.

Ahead of a WPF job interview last year I thought I’d freshen my UI skills by making a small application over the weekend. Taking on board why the previous team Hackathon finished incomplete, I adapted my approach to use the above suggestions. Being a solo project, Suggestion 2 practically comes for free. I’m only writing code with myself, using technologies that I understand. But I created the initial solution to be extremely siloed. I adhered strictly to the MVVM design pattern associated with WPF and used the Caliburn.Micro framework to create dynamically loaded UI modules.

But Suggestion 1 is tricky coding on your own. Can you dial that MVP back even further – it has to be so simple that you can achieve everything you set out to do in a weekend. I decided to simplify the problem and make a single player football manager.

My memory of that weekend from over half a year ago has gone but the second attempt went far better than my contributions to the first. I have so much still to do before I have a working, launchable application. But the weekend of the second attempt created a small, fully functional simulation of a football league. The additional UI elements have come slowly but the basic working end-to-end model has remained. Each time the code is dusted off after a break of a couple of months, the separated structure lends itself to added functionality in easy, distinct phases.

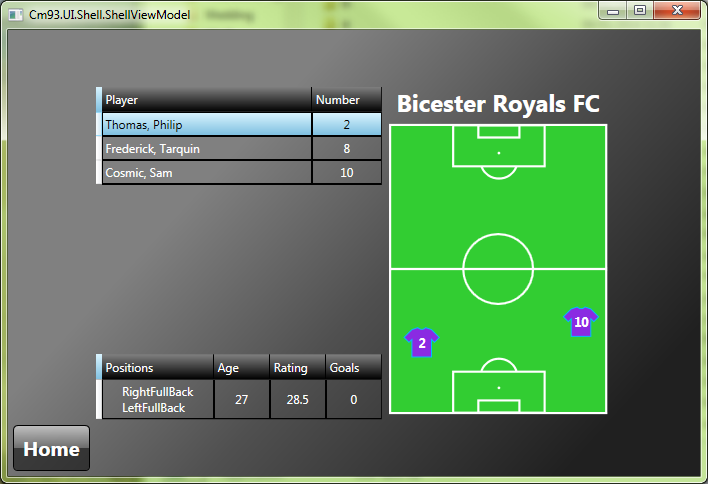

To consider what a real MVP looks like, compare the Team screen of the MVP with the current version.

Minimum

Minimum

Not Minimum

Not Minimum

Even now it’s still very much a work in progress but I’m pleased with how much I further I pushed the project over the holidays. I’ve put my Football Manager work-in-progress on GitHub to act as another tool to encourage me to continue with it in 2014. All the best for your future Hackathons.