Why 5 Whys isn’t enough

5 Whys is a prevalent engineering process in modern tech companies. When your company has operational incidents (and even the biggest and best ones do), 5 Whys is there to find the root cause, which in turn yields the next steps to make sure those incidents don’t happen again.

I could tell the engineering culture of the company needed work when an internal team had an outage related to an expired SSL cert. It wasn’t the outage that made me concerned; it was the attitude of the team who had the outage.

“What steps have you taken to make sure this doesn’t happen again?”

“We’ve updated the SSL cert. We’ll make sure we keep it updated in future.”

“…”

Holding an operational postmortem, incident review, incident retrospective, or whatever you call it, is the cornerstone of good engineering culture. The cornerstone of a good incident retrospective, is getting to the root cause of the reason why the incident occurred in the first place. When you have the root cause, the remedial actions which will protect your users against the same mistakes reoccurring, pretty much write themselves.

5 Whys is such a common method of finding that root cause, that in many incident retrospective templates the section heading is named The 5 Whys. The rationale is that 5 levels down of asking “Why?” will lead to the real reason, whereas asking one, two, or three whys, simply wouldn’t.

The simplicity of the practice is part of its power – it takes only a couple of minutes to explain how to use it. As is often the case, the greatest strength is also the greatest weakness. An enthusiastic engineer with a willing mindset can write a subpar incident review document which fails the remit of ensuring similar incidents don’t happen again. The ease of adoption of 5 Whys shortcuts training someone to the true goal of performing root cause analysis. 5 Whys will never be enough. Specifically, there are two fundamental flaws that lead to failure:

- Malicious compliance

- Non-linear root causes

Five is not a magic number, it’s a heuristic. Making it down five nested reasons as to why something happened could come after long introspective thought, and careful research, or it might just be throwing five baby steps at the wall, tidied up by some Gen-AI bot. Malicious compliance isn’t necessarily executed with malice; it could as easily be ignorance or haste.

Consider the team above which allowed their SSL certificate to expire.

- why did the authentication fail?

- the SSL certificate expired

- why did the certificate expire?

- no one renewed it when it was supposed to be renewed

- why didn’t anyone renew it?

- the team was busy with work related to project Goldqueen

- why were they busy with other work?

- there were more high-priority tasks than the team had capacity

- why was the team out of capacity?

- the team doesn’t have enough engineers

It hits the requisite number of whys, while giving no analysis into the procedures within the team for their operational responsibility, or ownership of the problem, or accountability regarding the incident.

Issues of quality can be addressed with gates e.g. an experienced disinterested engineer, say, one from outside the team, has to approve the 5 whys before the process can be closed. I’ve seen a new CTO bring in an ‘attack-dog’ Distinguished Engineer to take personal responsibility for ensuring the quality of every post incident report met the expected standard. Regardless of the methodology, this is good practice, and needs to be reviewed periodically to ensure standards haven’t slipped.

This is still not enough though. 5 whys analysis is linear, and locks the author and reader into a single path for the cause of the incident. Consider the following situation where the author arrives at the office soaking wet:

- why were you soaking wet?

- I was in the rain for 10 minutes without shelter or protection

- why were you out in the rain?

- I had to walk 10 minutes back from lunch to the office

- why were you so far from the office?

- I went for lunch at Shenanigans, which is half a mile from the office

- why did you go there?

- I love the mozzarella cheesesticks and goofy shit on the walls

One answer short of five, but the essence is clear: the ambience and snacks a restaurant offers is important to the lunchtime experience. If they could relax that constraint, or find somewhere similar that’s nearer to the office, they would be less likely to get soaking wet in future. But did you spot the implicit conceit in the first why? The sentence is made up of multiple clauses: which one are we asking why to?

[I was in the rain for 10 minutes] [without shelter or protection]

The subsequent thread of whys, completely ignores the second half of the first sentence, discarding valuable root causes. Let’s try again and focus on the other clause in the first answer.

- why were you soaking wet?

- I was in the rain for 10 minutes without shelter or protection

- why didn’t you have shelter or protection?

- I was walking outside without a jacket or umbrella

- why didn’t you carry outdoor protection?

- I didn’t bring any to the office in the morning

- why didn’t you come prepared leaving your house?

- I misjudged the outlook of the weather as clear and bright when leaving for work

- why did you misjudge the weather?

- I live in Scotland, and I really should know better by now

Completely different root cause, but no less valuable. The author should reconsider their location of lunch venue, and they should also ensure they come to work prepared for bad weather. Without acknowledging the non-linear paths for incidents, 5 Whys won’t find both root causes.

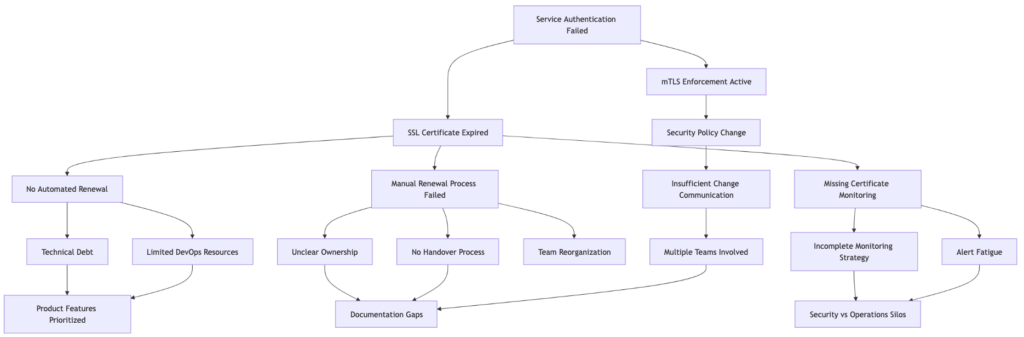

Once you realise there could be multiple paths, your root cause analysis isn’t one path, or even two, but rather it’s a directed acyclic graph. Revisiting the original SSL cert expiry for a service which requires mTLS connections, consider the following root cause analysis as an alternative to 5 Whys. This yields a goldmine of root causes, which makes preventing future incidents much more likely.

graph TD

A[Service Authentication Failed] --> B[SSL Certificate Expired]

A --> C[mTLS Enforcement Active]

B --> D[No Automated Renewal]

B --> E[Manual Renewal Process Failed]

B --> F[Missing Certificate Monitoring]

D --> G[Technical Debt]

D --> H[Limited DevOps Resources]

E --> I[Unclear Ownership]

E --> J[No Handover Process]

E --> K[Team Reorganization]

F --> L[Incomplete Monitoring Strategy]

F --> M[Alert Fatigue]

G --> N[Product Features Prioritized]

H --> N

I --> O[Documentation Gaps]

J --> O

L --> P[Security vs Operations Silos]

M --> P

C --> Q[Security Policy Change]

Q --> R[Insufficient Change Communication]

R --> S[Multiple Teams Involved]

S --> O