The Future of Education

Education is changing in a big way. Whether you’re still in the education system or someday going to have children who will, it’s of prime importance you learn just how it’s going to change.

Pass rates are going up in the most important school exams, namely, the ones that determine whether a student qualifies for university or not. It’s at this point where education stops being in a sense “free” and has to be evaluated as a value proposition – does the benefit of going to university outweigh the financial cost? Despite this being a Scottish blog, I’m going to look at the qualification used in the rest of the UK: the GCE Advanced Level or more simply, A Level.

A change in the 1980s brought on by an increase in the number of students staying on at school beyond the age of 16, resulted in a need to change the previous system that partioned grades according to a yearly curve. That is, prior to 1987, the top 10% of students in a given subject in a given year were awarded an A grade. After 1987, the bar was set independently which in theory would allow more or less than 10% of the student population to gain an A grade.

However, for reasons this blog post won’t go into, the band of A passes went up, and continued to go up.

Grade Inflation

There is a saying in finance that the greatest invention in the world isn’t the wheel but rather compound interest – sometimes apocryphally attributed to Albert Einstein. The reason it’s a big deal is that small and constant increases don’t feel particularly painful at any one time increment, but their accumulative effect over time is astounding.

The Rule of 72 is a shorthand method for determining how many years it will take a give interest rate to double your money. For example, a 6% return will double an investment in roughly 72 / 6 = 12 years. £1 invested for 100 years at 6% will become over £439. Small, constant increases result in massive changes over time.

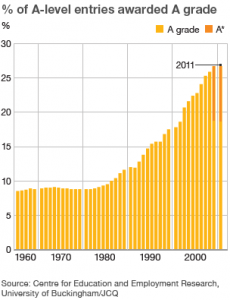

Consider the chart below taken from the following BBC article,

The change in pass rate for an A grade from one year to the next looks to be no more than 2% in any one year. And yet, from the beginning of the 1990s to the present day, the chance of a random student gaining an A grade in a random subject has become more than twice as likely.

Given that there are twice as many A grade students as a proportion of the student population today as there were twenty years ago, there are two extreme conclusions regarding the band of A grade exam passes: either the education system is twice as good at teaching as it was twenty years ago, or the exam has become twice as easy to pass.

There’s likely a combination of the two at work but the size of the difference strongly suggests a significant proportion from the second column.

The Harm of Grade Inflation

Without even looking at how teaching has changed in the last twenty years I hope I have avoided a bit of a red herring and you agree that grade inflation has taken place to at least some degree. What is the harm of this?

Moving the goal posts will always have follow on consequences. The recipients of A grade passes at A Level are likely to go on to university. These institutions now receiving a greater number of successful candidates will realise over time that the quality of an A grade student is not as high as in previous years and they have some choices to make.

They can (a) raise their admission requirements to require higher grades than previously*, (b) retain their admission requirements but award more lower degree classifications as appropriate e.g. more Lower Second Class passes than First Class or (c) like the schools before them, pass on the grade inflation buck and award similarly lower standards than the years before.

Where does this chain end though? Eventually, the products of the education system are individuals who join the workforce and companies are a lot more shrewd, and quite frankly, a lot more blunt about what will fly and what won’t. Rather than accept that roles previously offered to graduates who attained an Upper Second Class degree aren’t quite as good as those from a few years back, they quickly learn to request a First Class degree the next time a similar job opening is required.

The result of this final leveller? The monetary value of a degree is lessened, and is lessening further, with time.

*the reason why A* (A-star) grades were introduced – this screams grade inflation to me.

The Value of Higher Education

The increase in population coupled with the grade inflation that is producing even more graduates has two harmful consequences. The first is damage to the structure of academia itself – the university institutions that fuel and fund research by teaching students (I’ll come on to this more in a moment though).

But for the average student who has realised that the worth of a degree is constantly decreasing, this is a shock to combine with the fact that the cost of obtaining one is constantly increasing.

The point by the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government is made repeatedly that the loans required to pay for the ever increasing tutition fees need only be repaid once the graduated student earns a reasonable salary. However, the premise of this statement is that the act of obtaining a degree is worth it in the long run because it will allow the student to earn more in real terms than if they only had A Level qualifications. The double pinch is constantly gnawing away at this argument – tuition fees only ever rise, the worth of a degree only ever falls. The estimation of whether the degree will ever truly pay for itself becomes a harder and harder decision to call (especially for students interested in non-vocational subjects or those on the cusp of qualifying for their place).

As an example of how staggering the numbers are, for a student paying £9,000 per year in tuition fees and also taking a £4,000 per year maintenance loan (£39,000 in total) who enters the workplace earning £25,000, they will spend the next 25 years paying off a sum of over £100,000. It will take ten years until their payments actually start to reduce the debt in real terms (these numbers produced using the official government repayment calculator).

Academia is a Pyramid Scheme

To swing back to the damage done to academia by the prolific growth of university places, a pyramid scheme has fomented in the world of post-graduate research.

Though some academics enjoy the teaching aspects of their job, most are in it for the research – striving to push forward understanding in their narrow field of expertise. Some advances are incremental steps whereas the most profound are often large departures from the way that things are currently done or about how subjects are traditionally thought.

These large departures are risky on the part of researchers – they take a large amount of work, moreover a lot of time, to achieve. The system of tenure exists in academia partly for this reason: academics need to be secure in their position in order to expound on controversial works or unexplored methods. But the tenure system gives an amount of time linked to longevity rates. Lecturers who are awarded permanent positions for life in their thirties will be around for decades to come and despite the increase in undergraduate student numbers, university bursars well understand the financial implications of having too many of them on the books.

From the House of Commons Library (Standard Note: SN/SG/4252 [PDF]), in 1970, 51,189 students were awarded their first degree. Since the promotion of former polytechnics to award degrees, that number rose by nearly a factor of five to 243,246 in 2000. Even in the last ten years that number has risen considerably to 350,800 by 2011. All these extra students have required lecturers to teach them. But also they have been inspired to enter the world of research themselves.

What started as a minor warning in 2003 that perhaps working towards a PhD might not be the smartest move in the world, has burgeoned into a full-scale, red flashing beacon warning not to go near.

In trying to explain to someone what the problem is with the time of your career between being awarded a PhD and becoming a lecturer, I could only compare the process of surviving by repeatedly requiring a post-doc funding grant (typically 1-3 years) to playing Sonic the Hedgehog. No matter how hard the average postdoc student works or how brilliant they are, most won’t make it.

Alternatives to University

The postgraduate cul-de-sac is a symptom of the increased size of the higher education system and, while tragic for those who are a victim of it, isn’t the main focus of what is going to change with the future of education.

What is becoming apparent to postdocs (that there aren’t enough lecturer positions available) will soon enough be clear to those with degrees looking for graduate jobs – there aren’t enough graduate jobs i.e. jobs that pay well enough to make obtaining a degree cost effective.

Students must honestly be introspective and consider whether they might be harming their future options if they’re not confident enough in their ability to get a good degree classification. Those who don’t want to take the risk will be looking for alternatives. Enter the MOOC.

Massive Open Online Course

Massive Open Online Courses, or MOOCs for short, are the natural next step from courses like those being offered by the Open University. They use a wide variety of technologies to save yet more cost and scale to much larger class sizes.

Rather than have a bricks and mortar institution that pays for classrooms, lecturers, labs, teaching assistants, libraries and books, invigilators and examinations – technology is used to strip back to the bare essentials: a small teaching team; course content in various media forms; automated exams and assignments; all accessed by the student online from anywhere in the world.

The benefit is two-fold. On the one hand, a lot of the overheads are removed by technology. Buildings are replaced by web servers. But the other is more striking. A university course might be taught to a few hundred students. The MOOC template, once in place, can teach a course to a few hundred thousand students.

If this is the first time you’ve heard of this concept I appreciate scepticism. However, this is not a theoretical idea, this is already happening. And it’s not just an experiment, many of the problems or shortcomings you may be imagining of such a distributed system have been considered and solved. Furthermore, for some subjects, notably computer science, this can be a genuine alternative to going to university.

Computer Science: Degree Not Essential

For someone with two degrees in computer science, I remember once not being too fond of the suggestion that you didn’t even need one degree to get a job as a software developer. But now I see the true beauty of the lack of barrier to entry.

Considering how hard it is to tell if someone’s a good coder or not, it’s fairly common for programmers to have their own code repository for potential employers to view (like mine here). More and more, programmers who can prove that they have the skills and knowledge required to be good software developers can find graduate jobs without having a degree.

For now at least, technology companies are leading the way but as the popularity of MOOCs increases, it won’t be long until other disciplines recognise non-traditional qualifications. I’m not saying a MOOC certification will match a Russell Group degree, but it doesn’t need to – it just needs to provide value, it needs to provide an alternative to a debt of £39,000.

Coursera

I’m a 30+ employed graduate software developer and I’m part way through my second MOOC with Coursera. The current one is Startup Engineering, a course about the technology, business, philosophy and even history of startup companies. I’m finding it fascinating. Taught by Balaji Srinivasan and Vijay Pande, it’s a course from Standford University, a very prestigious instiution and by lecturers who have a proven track record as startup founders.

Before that though I sat a six week course on Music Production taught by Loudon Stearns from the Berklee College of Music. I was pleasantly surprised to find that such a course existed and that its creator had not only found a way to test the students’ theoretical knowledge, but a system of peer review that successfully allowed a scaled marking of project assignments.

In addition to Coursera there are others such as Online Courses, and a UK based collective of universities Future Learn. The breadth of courses available for free is genuinely surprising and, on a human level, uplifting to know that such resources are out there.

Education as a medium

My argument thus far is one of financials. The cost of traditional degrees rise, but at the same time are worth less. Technological improvements mean that it’s possible to improve the efficiency of how university level education is taught via MOOCs. I contend that market forces – brought on by the decisions of those who have to bear the cost of their own tuition – will see the rise of MOOCs as the primary method of higher level tuition in future.

If you don’t agree with me, consider this. Who do you think of first when I say “The Merchant of Venice”: William Shakespeare or the actor who played Antonio in The Globe Theatre in the 16th century?

Who do you think of first when I say The Shawshank Redemption: Tim Robbins who played the lead character, Andy Dufresne, in the film adaptation or Stephen King, the author of the short novel it was based upon?

The medium of the art form is critical as to what is considered important. Novelists and playwrights have always been important but actors more so only recently, historically speaking, because the medium of cinematography is now as accessible as the book has been for centuries before it. I can as easily watch a film on my phone as I can read a novel.

Similarly, I have no idea who the First Violinist was at the premiere of Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Festival Overture, but with radio, vinyl, CDs and now mp3s – the performer takes precedence over the composer.

Some people will always want to see something in the flesh but once the medium is perfected, scale will always win. The lecturers of the future will not be the ones living in the same city as you, but the one who have the best worldwide reviews. And when I consider how few lecturers there were who truly captured the imagination and conveyed their passion for a subject, the more I think there’s a lot of merit to a system where the best teachers globally are the ones who teach higher education.

The Future of Education

I’m not saying which system I think is best – there are positives and negatives with each. I simply believe that online teaching is the future and, apart from the world’s leading universities, this shift will force many higher education institutions into decline. Regardless of whether you’re convinced by my arguments or not, I have one request to make of the reader.

When I was an undergraduate, there was a retired man called John who had chosen to spend some of his final years, likewise, reading for a degree in computer science. There was an element of choice each semester between which courses students could sit. I remember seeing him in a lecture for a course he was not enrolled in and I asked him, “What are you doing here John, you aren’t taking this course?” He replied with, “Yes, but it sounded interesting, I want to learn about it.”

Massive open online courses are freedom, freedom to learn. John had to invest a lot of time and money to get a degree just so he could dip into an extra course or two that was of interest to him. MOOCs give back that extra bit of freedom to learn for learning’s sake. The request I make is simply to look at the courses available. If something piques your interest, give it a go. Perhaps you’ll think it’s the future of education too.