Before you learn to program

How should you begin to learn programming? What language should you pick? What are the long term, safe bets you should ensure you pick up so you're ready to succeed over the next ten years?

These are the wrong questions to answer. Programming is the valuable, practical skill but the discipline that enables and supports it is Computer Science. Begin from that position and the lessons you learn will hold not only during the lifetime of the programming languages you choose, but throughout your own life as well.

But Computer Science though, that's hardly the right place for a beginner. Without knowing any programming how can we appreciate the motivation behind finite automata, Turing completeness, complexity classes, algorithm analysis, recursive design, data types, sorting routines, graph traversals and tree searches?

Again, wrong. Computer Science just needs to be introduced more simply.

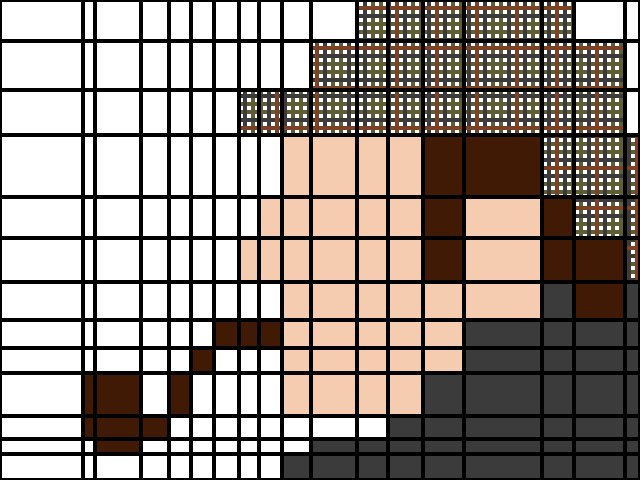

Look at this picture. It's a visual cue to aid remembering the core themes central to everything to do with Computer Science.

It is a representation of the famous fictional detective Sherlock Holmes, in the style of the painter Piet Mondrian. More on this later though.

Logic Gates

Before diving into programming languages, let us consider the lowest possible level of computation: logic gates. While it's possible to explain the semantics of what a logic gate does, programmers don't realise how instinctively they already have most logic gate's truth tables memorised.

First thing's first though - what's a logic gate?

A logic gate is a like a black box that performs a calculation. It takes a fixed number of inputs and has a fixed number of outputs. Logic gates are used to express boolean logic expressions which mean they deal only with boolean inputs and outputs i.e. an input or output value can only be 0 or 1.

One of the most common logic gates is the AND gate.

It has two inputs, A and B, and one output X. It works in a similar way to the English word 'and'. For example, consider the following four responses to the question, "Did Alice and Bob go to the cinema last night?"

- "No, neither of them went."

- "No, only Alice went."

- "No, only Bob went."

- "Yes, both Alice and Bob went."

Here, we could model our English sentences using the logic gate if we map the inputs and outputs being 0 or 1 to specific outcomes. So, if A is 0, that means Alice did not go to the cinema last night. If A is 1, that means Alice did go to the cinema last night. The same rules apply for B and whether or not Bob went to the cinema last night. The output value X, of A AND B, is 1 if both Alice and Bob went to the cinema last night, otherwise it's 0. Writing this down purely as zeros and ones, is called a truth table.

AND Gate Truth Table

| A | B | X |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

While the English sentences used above help try to explain the semantics of what a logic gate is doing, the truth table is brutally logical. A truth table doesn't so much explain what a logic gate is doing, it tells you what it does.

This is very handy for those using logic gates when the Engligh language definition might by subtly different. Consider the OR gate.

Its structure is identical to the AND gate. It takes two binary inputs A and B, and has one binary output X. It also corresponds to the English word 'or'. Consider these four responses to the question, "Would you like Apple juice or Blackcurrant juice?"

- "No, I would like neither."

- "Yes, I would like Apple juice."

- "Yes, I would like Blackcurrant juice."

- "Yes, I would like both."

Generally speaking, when someone asks you an 'or'-like question, they only consider three outcomes: the first option, the second, or neither - it rarely means both options.

There exists a logic gate that can model what is generally meant when the word 'or' is used in English sentences. This logic gate is called XOR and is pronounced "ex-or" and is short for exclusive or. Consider the responses to the question "Would you like Apple juice XOR Blackcurrant juice?"

- "No, I would like neither."

- "Yes, I would like Apple juice."

- "Yes, I would like Blackcurrant juice."

- "No, I'd actually like both, please. If it's not too greedy."

Essentially it means you can exclusively have one option or the other but not both. For completeness here are the truth tables for OR and XOR.

OR Gate Truth Table

| A | B | X |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

XOR Gate Truth Table

| A | B | X |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

Logic and Understanding

This subtlety of understanding is very important to programmers. Computer programs are too complicated for the entire state of all their inputs and outputs to be represented - there are just too many combinations to enumerate. Instead, programmers hold mental models like the English word definitions of AND and OR. When programs don't work as expected though, programmers have to narrow down exactly where the problem is. They have many complex tools to aid them, but ultimately it comes down to the programmer's understanding of logic and the rules being used.

In times like this, being able to construct a truth table to verify what the output should be for a given input allows the programmer to logically and methodically discover the location of the fault in a program.

A Binary Adder

Regardless of the programming language you begin with, the required skill set is similar - it's about how you use the available features of the language to solve problems. In the beginning the process will feel difficult, unclear, perhaps even incomprehensible. Practice will help the most.

This is stated in advance of the example below in case the train of thought is not obvious and thus hard to follow - don't worry, re-read it again later after you're more familiar with programming and it will be clearer. The challenge we're about to solve is to create a multi-digit binary adder using only AND, OR and NOT logic gates. The AND and OR have already been seen, and the NOT gate takes just one input and outputs the inverse.

NOT Gate Truth Table

| A | X |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 |

A simple logic gate for adding single digit binary numbers will require two inputs and two outputs. The inputs A and B can be 0 or 1. The outputs C and S are also either 0 or 1, and together they represent the sum of A and B. Here is the truth table for what the binary adder should create (S stands for Sum, and C stands for Carry).

Single Digit Binary Addition Truth Table

| A | B | C | S |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

Hopefully you can see that the C column can be created by calculating A AND B, and the S column can be created by using A XOR B.

Unfortunately, even though we know what an XOR calculation looks like, we don't know how to create it. Every single computer device you access in your daily life whether, a desktop PC; laptop; smartphone; right down to a flashing LED bike light; they're all built with logic gates. And at a sub-microscopic level, it's common that we may implement certain logic gates, such as XOR, using other logic gates that are, for example, cheaper to make.

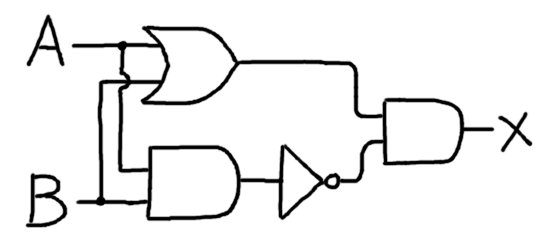

We can make an XOR gate by creating an intermediate stage which we'll call A' which is A or B, and B' which is not (A and B).

XOR using ANDs, ORs and NOTs

| A | B | A or B | not (A and B) | A' and B' |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

By performing a couple of stages and combining the result, an XOR gate has been created using two AND gates, one OR, and a NOT.

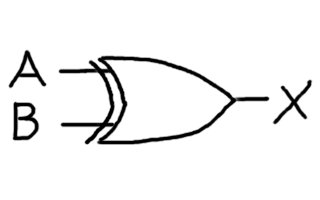

The 'dot' junctions split the A and B inputs so their value can be used twice. If we want an XOR gate in future, we know we can make one using the above combination of logic gates. However, to make things less complicated than they need to be, if we want to use an XOR gate in a new diagram we'll use this symbol for XOR instead.

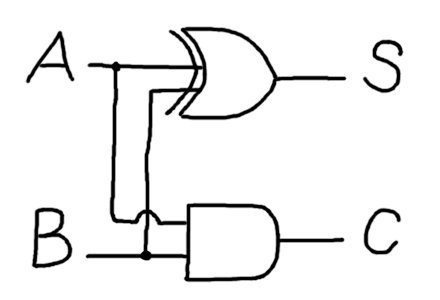

Now when we see this symbol we don't have to remember how it was made, just that it's an XOR gate. We can now create a binary adder circuit like so.

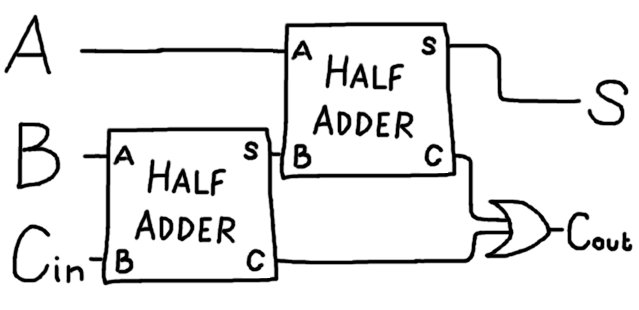

This circuit is known as a Half Adder. Combining two of them we can create what's known as a Full Adder. A Full Adder, in addition to the two inputs A and B, also has a third input which is a Carry input from another adder. Note how the diagram above, is simplified to be a box labelled Half Adder below, with the inputs A and B, and the outputs S and C denoted in the corners. Again, because we know what it does, we don't need to be concerned with how it's made when we're using it to build something else.

Here is the truth table of the Full Adder. We've renamed the original C to Cout to denote that it's an output Carry, and the new input as Cin to denote that it's an input from another Full Adder.

Full Adder Truth Table

| C_in | A | B | C | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

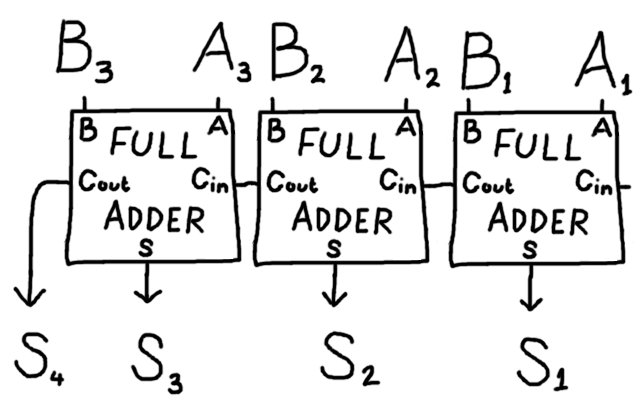

We can now chain together several Full Adders like so to create something that can add together binary numbers as large as we want.

What seems like such a simple task, adding numbers together, has been accomplished using two techniques that are central to all areas of Computer Science and programming. It's time to revisit that picture.

Logic and Abstraction

Sherlock Holmes is a fascinating fictional character. Though deeply flawed, his adherence to logic and deduction mean that he has a clearer understanding of the rest of the world than those around him. It is his mastery of logic that makes him formidable.

Piet Mondrian was a pioneer of the abstract art movement. Abstract art, without showing a completely accurate or faithful representation of the subject matter, can communicate an idea any bit as rich as a painting from the more exacting classical era. The harsh lines and solid colours above are completely missing from the natural world, and yet we can make out the famous deerstalker hat and pipe of its subject.

An abstract representation of the master of logic - a visual cue to the foundation of Computer Science.

Logic. It's about understanding the rules, understanding how something works. It's about being able to predict the outcome because you know the model. Abstraction. It's about knowing how things fit together, knowing the layout or architecture. Being able to simplify in order to more easily navigate from one place to another.

Logic and Abstraction combine to aid us as humans. When we mentally step through the process of how two multi-digit binary numbers are added together, we don't think about the AND, OR and NOT gates. It's too complicated at that level, there are too many of them. We mentally model the process in terms of Full Adders. We take the complex, label it simply, and lift our understanding up to a higher level. Our understanding of logic helps us to understand how each level of abstraction works, and the abstraction itself keeps it simple enough to be able to understand not only the model as a whole, but every single part of that model.

Solving problems and understanding systems with logic, reducing complexity and conceptualising the whole using abstraction. This is the skill that will stay with programmers always, and the one they should learn first.