Software Engineer Dystopia or Hegemony

I've finished rewriting my 15 year WordPress blog from the ground up as a static Next.js site. This was attempt number three, and I'm happy relieved to say this one was successful.

Early in my career, my default was to over-engineer. When I started a blog in 2011, I wanted to own the entire stack myself, and despite knowing nothing about CMS tech, I wanted the most configurable solution available. I chose Drupal. After publishing 26 blog posts, I made the sensible switch to the more lightweight WordPress. Still requiring a server and database, and built on PHP (a truly terrible programming language), it lifted much of the admin complexity, and had a slick, intuitive UX. I had to drag around those 26 earlier blog posts URL slugs, but otherwise I was happy I had the best tech trade-off available.

Skyscanner war stories

In 2017 I became the manager of SEO pages for Skyscanner, leading the Hamilton team, named after Margaret Hamilton. It was in that role that I learned what SEO pages should be: a free user acquisition source, made by creating simple, performant, templated pages with valuable content, discovered via search engines. Skyscanner's SEO pages were neither simple nor performant. There were more than 40 different landing page types, spread across three production systems: Mater, PageBuilder, and SEO Pages. Mater aka Old Web Framework (OWF) aka The Website, held the majority and was the oldest client facing production service in the company at the time. It was the old frontend monolith that used to be the entire website: Flights, Hotels, and Car Hire, as well as bespoke flight travel searches such as Browse and Everywhere. As the company matured, this monolith was broken up into microservices. Mater did less and less, as these individual services were incrementally decoupled to the New Web Framework (NWF), an HTML templated solution using a Varnish reverse cache proxy. Yet all of Mater still needed to be operationally live, to serve the SEO pages responsible for 10% of customer acquisition, without additional tithes payable to FAANG.

At the start of 2018, faced with a lack of momentum at pushing Skyscanner over the line to complete the data centre to AWS cloud migration, engineering leadership gave a clear message: get everything out of the data centres, get everything off .Net on Windows, and into open source Node, Java, or Python running in AWS, by July. Back when the Mater monolith was the shiny new website, Skyscanner was predominantly run on Microsoft: C# ASP.Net MVC backends and MS-SQL databases on Windows, Word, Excel, Outlook, Sharepoint and Skype for collaboration. By the end of the decade, the company wanted everything open source, running on Linux and in Amazon's cloud.

Developer Enablement teams had been running for a while and provided fantastic tooling to make the transition easier:

- m-shell: a set of opinionated, batteries-included Dockerimage files, with library support for http middleware, logging and telemety

- shared cluster: a horizontally scalable ECS compute cluster in which to run your containers

- slingshot: a continuous deployment pipeline for the above cluster, with configurable telemetry-based automated phased canary releases

- gateway: a kong API gateway with easy public endpoint routing, and throttling support

If you knew how to use all of the above, you could have a "Hello, World" webservice publicly available in production, from nothing, in 10 minutes. Compared with the recent past where you'd fill out a ticket, wait days, and maybe have to nudge people to get server provisioning over the line, the immediacy and effectiveness of the automation was astounding.

This fit a specific type of client-server microservice pattern though, which wasn't the right fit for SEO pages. Search engines care about reputation, volume and performance. Skyscanner's domains had great reputation, and the sky was the limit for how many pages we were allowed to publish to Google. There were literally trillions of possibilities combining the airport, airline, city, country or route landing page types, with each locale, market and currency. How good your pages are is reflected in how well search engines rank your content. The exact secrets of the PageRank algorithm are a well hidden, but you can gain a lot of insight from what Google say is important. This is one of the reasons why their page ranking tools are so important.

Search engines don't just care about uptime, but wanted SEO pages served quickly, with fresh data which people wanted to see. Today, the terminology has evolved to Largest Contentful Paint, Interaction to Next Paint, Cumulative Layout Shift. Back then the priority was Time To First Byte, and DOM-Ready Time. There are also trade-offs regarding JavaScript on pages. Today Google will queue pages with a 200 response for rendering using a headless Chromium browser, but this wasn't always the case. If your page needed to run some slow JavaScript to fetch a price, it wouldn't necessarily make it to the search results. "Fly from LHR for only £12" is a much more compelling search result than "Cheap flights from LHR".

Mater was an old Asp.NET MVC behemoth. It was slow. It had 20 downstream service dependencies, which you were lucky to be documented API calls. Some were internal network hacks to run a stored proc on an MS-SQL server. The cache hit rate in the shared Varnish instance was less than 30%. Google had introduced Google Flights and was returning an interactive app for some search queries at the top of their results. They'd also moved from two paid links at the top of search results, to three, further diluting the impact of unpaid SEO pages.

We were competing on historic reputation, but the slow pages were hurting that reputation. More and more of the biggest search terms were falling further down the search results, meaningfully hurting the company's bottom-line. The SEO pages needed a different architecture, something more like the choice of tech stack acquired with the purchase of US based start-up Trip.com (not to be confused with the Chinese company CTrip, which had acquired Skyscanner). Trip.com had a simple stack with landing pages published to a Content Distribution Network (CDN), sitting in front of Apache SOLR, which cached results from a Rails and MySQL backend. The key feature which Trip had, that Skyscanner did not, was that their CDN had a cache invalidation API.

There are two hard problems in computer science: naming variables, and cache invalidation. Storing data in a cache is cheap and fast, but risks serving stale data. If we wanted performant pages, we needed our pages to start being published to a CDN. These take your static assets (predominantly HTML, CSS, and images) and redundantly publish them at multiple geographic locations all over the world, so they're nearer to your customers. These can be expensive if you're storing a lot of data, or updating frequently, but they are second to none in delivering static data. Skyscanner had been using the CDN incumbent, Akamai, for years to store images and stylesheets for the main products, but newer CDNs were on the scene with a killer feature: cache invalidation. If the cheapest flight available for the most popular route changes every hour, you want to publish an update to that landing page every hour. How long though is dynamic — you can't set a global cache window and have that apply to all page types and markets. The ability to dynamically invalidate a cache with an API call, was key.

Akamai were playing catch-up; they did have an API, but it was hard to use and not integrated with the Developer Enablement teams tooling. There was no easy way to recreate the dozens of different page types in Mater using the new Trip stack. The Trip stack didn't have the deep integration it needed with key Skyscanner services (URL, headless CMS, translation etc.) to get working pages on Skyscanner's domain. The Skyscanner ecosystem needed much written from scratch. The team started on the most profitable landing page: routes e.g. https://www.skyscanner.net/routes/edi/lond/edinburgh-to-london.html. Eight years on, you can still see the service name, Falcon, and the team name, Hamilton, in the HTML today. Most of the 6 month budget was taken filling in the blanks on the Skyscanner side. It was obvious, even with more engineers, we would never recreate the pages in time.

I'm a big fan of the simple heuristic of choosing your flexibility: features, budget, timeliness. If a project cannot be delivered, you have to flex on at least one of those criteria. With the data behind us that the current approach would not successfully complete the mid-2018 deadline, senior leadership approved the change of direction. The team built Bluejay, which actively cached every page requested by users, in S3. This was a painful product trade-off, because the data would always be stale from that point, but at least we'd be serving pages without needing a Windows based service running in a data centre. This meant removing all dynamic price data.

Executing with the new long-term S3 cache approach, we successfully completed the project on time. We needed to borrow more engineers which we got; we had made data on many pages stale, hurting the efficacy of the pages for regional marketing teams; but we made the data centre migration timeline enabling the savings of millions of pounds annually from full data centre switch-off. I learned a lot from this experience. Mostly, plans don't survive first contact with the enemy. We had great microservice tooling, and a newly acquired stack amenable for SEO pages, but neither worked within the timelines.

a simpler stack

My first love was always developing the computer program, not as much the systems, hardware or networks over which it ran. The unseen complexity of SEO pages, something I wasn't initially excited by the prospect of leading, opened my eyes to the variety in end-to-end distributed system design. This interest eventually led me to write an Infrastructure as Code stack in 2021 to host a TLS encrypted, CDN edge-cached simple static website. Sharing this on Hacker News, I got multiple valid questions about why you'd ever use this instead of Netlify, Cloudflare, or GitHub pages (all free)? To me though, I loved the control I had using AWS services which can all be automated. If you have a registered domain in Route53, AWS will provision all the services you need with one stack: CloudFront, ACM, Route53, S3. You only need put your HTML, CSS, and JavaScript in your S3 bucket.

My desire to own and automate more of the stack was because my eyes had been opened to the possibilities of a better tech solution that was also simpler. Different architectures for publishing websites beyond just monoliths and microservices. Jamstack was a relatively new architectural approach at the time, but now it's nearly a decade old. One of the best engineers at Skyscanner, Hugo, had a Jamstack site for his blog, as an open source project in GitHub. As soon as I saw it, my ongoing WordPress administration grew increasingly tiresome. I no longer accepted the annoyance of, say, the time I had to recreate my site from scratch because one of the WordPress plugins led to my site being hacked, as a reasonable price of maintaining my own blog. I knew I no longer had the best tech trade-off available.

One of the strengths of Hugo's site is its simplicity. I, however, did not want to compromise on some of the things I've built over the years. Categories, images, pagination, LaTeX formatting, legacy URL slugs, and especially, embedding Skyscanner's travel widgets in my blog, the first software product built from scratch, that I managed. Not wanting to cede any of this, I needed a clean, responsive design. Even more, I wanted chunked downloads and optimised images: I wanted to get perfect score's on Google's PageSpeed Insights tool.

My first attempt a few years ago died a death of complexity as I lost momentum reading docs and failing to make my mind up whether to upskill my CSS, or dive into tailwind. My second attempt earlier last year, with the assistance of GitHub Copilot, created a working site that I was happy with in almost all ways, other than performance. It was here I had the most frustration with generative AI tools, and their ability always to say, "Yes!" while ignoring your instructions. This recent third attempt, having used generative AI tools for two years, was successful in all ways. I'm happy I've got a pattern that I'm looking forward to using again.

The outcomes landed exactly as I wanted. The site looks good, and all the pages that were once typed in WordPress, now render from Markup. The images are optimised, the views responsive, the mathematics rendered in KaTeX, pagination, the categories, the travel widget, it's all there. Using my CloudFormation script, which has edge caching, Origin Access Control, and HSTS among other things, the PageSpeed Insights scores are almost perfect. I blog for my own personal interest, unbothered about views or ranking. There's technical satisfaction knowing the architecture is optimal for search engine preferences though, right down to edge caching providing perfect performance in the event of extreme spikes of virality.

The entire open source codebase of creating this blog that you're reading now, went from initial git commit to complete deployable site, in 2 weeks. The most satisfying part without a doubt, was how pleasant coding each task was. Being crystal clear on all the project requirements ahead of time, asking Claude to ultrathink how to split the work into small, deployable features, led to a ~30 task backlog. Coding for just 4 hours a day, progress was tightly scoped and visible, and time passed like it was nothing.

the theory and practice of legacy systems

In The Future of R&D Productivity, a talk at CTO Craft Con London 2025, Will Lytle described new organisational structures for teams working with generative AI. He described the new AI tools as being like having 1,000 junior engineers on demand. Vibe coding sells the idea that the engineer is no longer needed, but from my point of view, it's more important than ever to have experienced engineers. Use AI to go faster, of course, but slow it down enough to review and understand the code it outputs. I'm so happy with the codebase I have today. I haven't looked in detail at every line, but I understand the project hierarchy. I have challenged and questioned every change. I have argued repeatedly to remove noisy comments, to apply the DRY principal and use the centralised type structures because that's what they're there for. I have pushed back on complex code changes that looked to be put in the wrong place. After all that, something of quality has been created that neither myself, nor generative AI, could have delivered alone.

I have some solid ideas about how I can use generative AI to write code, and how teams could be organised, but it's not a solved problem yet. In Why Your CTO Might Start Coding Again, Dave Griffith argues that managers who have been one step removed from code for years, have a superpower when using AI because they have honed how to question and interrogate code they haven't written. Today code is developed by engineers, orchestrated by managers. The proposed future is code developed by AI, orchestrated by engineers. Managers, it's suggested, are well qualified.

The pudding is over-egged though. The code can be perfect, but it stills needs to be run; it still needs a team that knows how to operate and maintain it. When it comes to operational ownership and troubleshooting, anyone who has been in a multi-hour incident call knows just how tense, lonely, and stressful an environment it can be. Engineering is where theory meets practice. In Skyscanner, the company was well prepared for a data centre migration in 6 months, with exceptional developer enablement services, and newly acquired tech and talent. Well prepared everywhere, except for where it wasn't.

Looking at some of the other SEO page types like Flights From, Flights To, or Airports, they took well over a year to recreate, or were dropped entirely. This can be shown by looking at Internet Archive page caches and seeing whether they were served by Bluejay (cache of the old Mater pages), or Falcon (new microsite pages). Flights to Edinburgh captured on 19th January 2019 is serving a partially successful cache of the old Mater page via Bluejay. The next valid cache from 10th February 2019 shows the service returning the main page content is the Falcon microsite (you can search for these strings in the HTML). Similarly, the last Bluejay capture of the Flight from Edinburgh page happens on 26th March 2019, and is migrated to Falcon sometime between then and 2nd September 2019. The airports pages themselves are dropped entirely, with a 301 Moved Permanently redirect to the Flights To page e.g. the last Edinburgh Airport capture from Bluejay happens on 29th January 2021. These pages were supposed to be a fast-follow after the data centre migration. Like I said, plans don't survive first contact with the enemy. Systems which are too important to throw away, but too complex to reason with easily, are destined to be time sinks.

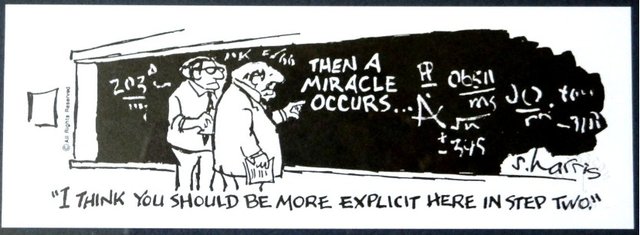

CTOs must correctly take the bird's-eye view. For the reasons just discussed, I sometimes think of this cartoon when they do.

Legacy systems are hard. Token limits in LLM lead AI tools to struggle with behemoth legacy systems. People are still using WordPress built on PHP. It took years of effort to get rid of all the remnants of that old ASP.Net MVC system in Skyscanner. Layering a complete set of AI tooling and organisation changes on top of legacy systems and legacy ways of working, makes this a race against time. Will the high-end microchips, power stations, and data centres be ready in time for all the companies that need them? Peter Zeihan doesn't think so. Will the AI companies find an economically viable commercial model in time before all the venture capital runs out? Cory Doctorow doesn't think so. I simply don't know. Right now, it feels foolish to think about working any other way than embracing the new AI tools that are available today, and organising around them.

dystopia or hegemony

In Lytle's talk about the future of productivity, he argued that the big competition for incumbents will be against companies started in 2026 who have AI at the centre of their development cycle. The implication is that these new companies will work in completely different ways, needing far fewer people. If this turns out to be true there could be an engineering dystopia (especially for the newest cohort) as that key property of our scarcity is lost. If the funding of AI companies bursts before enough established companies with legacy systems can evolve to a new way of working, Cory Doctorow discusses an idea for what will be left of value in the aftermath. He argues there will be optimisable base models that will run on a local development laptop. Mozilla are pushing for this strategy — running your own open source models instead of renting them from OpenAI or Anthropic — and argue that when convenience is a solved problem, people will choose open options.

Engineer political power came from scarcity. The layoffs, the path towards AI centric software engineer organisational models, are both trying to create the world where business owners retake the political power. Historically, this way is the norm. Developer Hegemony by Erik Dietrich argues for software engineers to follow the model of lawyers and accountants, being partners in their own firms e.g. something like Hermit Tech, co-founded by Nikhil Suresh, from the podcast Does A Frog Have Scorpion Nature?. Software engineers with access to their own tuned base models on standard spec laptops, makes the power of that model more exciting.

Like I said though, I don't know. Things are changing, the AI genie is out of the bottle, we won't work the same way again. But are the days over of senior engineers cursing as they manually hunt through a crash dump stack trace in a legacy service? I really don't think so.