Yo dawg, I heard you like functions

It’s hopefully old news to you all but the free lunch is over (NB this article is 10 years old). TL;DR – as we come up against the physical limits of how small transistors can be future computation gains will come from more processors, not faster processors.

We can already see this looking at the number of cores we have available in development standard laptops. Writing code that can distribute its workload across multiple cores will only become more important as time goes on.

As we move more and more services to AWS ensuring we get the most value for money by distributing workload becomes crucial. Like most things relating to programming, there is no single correct way to do so and I recommend researching the subject on your own e.g. try searching for CUDA.

By avoiding mutable state, functional programming can more naturally partition computation into mutually independent units. Many techniques for task parallelisation become available when the programmer is able to create code in a functional style. Most modern object oriented languages these days have functional programming concepts available (Python, JavaScript, Scala, Java 8 , C#, even C++!) so you can dip your toe in before diving straight into Haskell or F#. I hope this blog post will convince some of the die hard imperative OO coders out there (I know you exist, I’ve spoken to some of you!) that it’s no longer ok not to know your map from your reduce.

Concurrency vs Parallelisation

First, a minor digression to deal with some disambiguation. The “Free Lunch is Over” article I linked to at the beginning of this blog post uses the term concurrency where I’d say parallelisation. So what’s the difference?

Imagine driving a car while drinking a coffee and having a conversation with a passenger. You’re behind a red light in traffic so free to take a sip of coffee; you’re driving on a straight road and arguing about which was the best Coen brothers film; or you see a potential incident ahead and cease talking mid sentence to concentrate fully on the road. This is concurrency: handling multiple tasks at the same time with only one resource.

Imagine inviting your friends round to your new flat having beforehand procured several brushes and tins of paint. They may not be your friends for much longer but your flat will be painted quicker than you could manage on your own. This is parallelisation: providing the resources to distribute the collective workload between many workers.

Why the difference matters

You may be keeping up with the changes of your favourite languages and tech stack. Say you’re a JavaScript developer and you promisify all your Nodejs or browser code. Perhaps you’re a C# coder and you know to declare an IO-bound function as async. Maybe you’ve tried Go and are eminently familiar with Goroutines. These capabilities help you deal with concurrency, they do not help you parallelise computation.

Introducing Higher Order functions

A Higher Order function is one that takes not just data as a parameter, but also a function. The Higher Order function splits up the data parameter into smaller pieces and invokes the function parameter on these smaller pieces one at a time. The result of all these internal function calls is collated differently depending on which Higher Order function was used.

Example Higher Order function: filter

For C# programmers familiar with LINQ, you will know the filter Higher Order function as Where. Its purpose is to look at a collection (a sequence of elements) and discard all elements in that collection that don’t have a certain property. Say we have a Python list of data:

data = [1, 4, 0, 6, 1, 9, 5, 8, 7, 2]

We wish to know which members of data are greater than 5. To do so we construct a lambda function i.e. a stateless function that can be defined inline or stored in a variable.

greater_than_five = lambda x: x > 5

We can now treat the variable greater_than_five like a function:

greater_than_five(3) # returns False

greater_than_five(123) # returns True

The Python Higher Order function filter is called like so:

filter(greater_than_five, data)

The result is a generator that, once evaluated, gives us the following output: [6, 9, 8, 7]. That is, all the elements of data that are greater than five. The filter function invokes greater_than_five with each element from the list, data. Only elements that get a response of True are kept.

Solving problems with Higher Order functions

Imagine we have a data set describing programmers and their skill with a particular technology colourfully named red, green and blue:

| Name | Age | Technology | Rating |

| alice | 24 | blue | 86 |

| alice | 24 | green | 80 |

| bob | 20 | red | 76 |

| bob | 20 | green | 68 |

| charlie | 45 | blue | 96 |

| dylan | 32 | blue | 75 |

| dylan | 32 | green | 81 |

| dylan | 32 | red | 54 |

| evelyn | 29 | green | 83 |

| evelyn | 29 | red | 78 |

| francis | 19 | red | 64 |

Suppose we need to create a function that returns the most skillful programmer for each technology under the age of 40. This could be done in an imperative style like so:

name, age, tech, skill = range(0, 4)

def get_answer_imperative(_data):

answer = {}

for row in _data:

if row[age] >= 40:

continue

if row[tech] in answer:

answer[row[tech]] = max(answer[row[tech]], (row[skill], row[name]))

else:

answer[row[tech]] = (row[skill], row[name])

return {_tech: skill_name[1] for (_tech, skill_name) in answer.items()}

We could also implement this code in a functional style using Higher Order functions:

def get_answer_functional(_data):

return dict(

map(

lambda (_tech, rows): (_tech, max(rows, key=itemgetter(skill))[name]),

groupby(

sorted(

filter(

lambda row: row[age] < 40,

_data

),

key=itemgetter(tech)

),

lambda groups: groups[tech]

)

)

)

What’s the benefit of solving problems with Higher Order functions

The performance of the two implementations above are fairly comparable and essentially instantaneous. The benefit of using Higher Order functions comes when we move from working over a manageable data set to one that’s intractably large.

There will always be some limit to the size of the data that can be called using either of these functions. The key difference is that by using Higher Order functions, we separate the logic from the state and chain the necessary operations one after the other. The imperative implementation is a black box that cannot be broken up without refactoring; the functional implementation however can be split into multiple, cascading functions.

def get_answer_functional_4(_data): return filter( lambda row: row[age] < 40, _data ) def get_answer_functional_3(_data): return sorted( get_answer_functional_4(_data), key=itemgetter(tech) ) def get_answer_functional_2(_data): return groupby( get_answer_functional_3(_data), lambda groups: groups[tech] ) def get_answer_functional_1(_data): return map( lambda (_tech, rows): (_tech, max(rows, key=itemgetter(skill))[name]), get_answer_functional_2(_data) ) def get_answer_functional(_data): return dict( get_answer_functional_1(_data) )

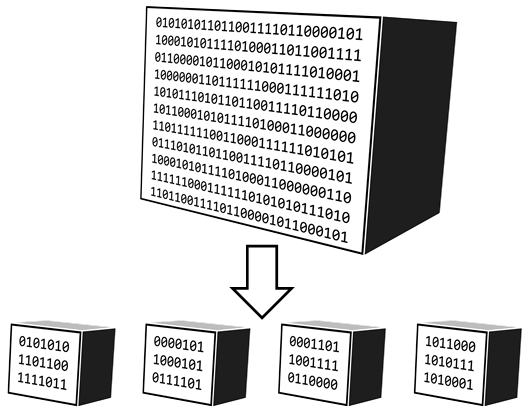

The intractably large data set can likewise be partitioned into manageable pieces

By changing the way we invoke the functional style cascading functions, we can call each in turn with the manageable pieces and merge the results (much like the merge operation in Merge Sort). The deepest function (get_answer_functional_4) is called first on each partition and results of each invocation are collated – the exact collation method depends on the Higher Order function in question. The process of partitioning begins again and the next function down is called with a slight modification:

def get_answer_functional_3(_data): return sorted( _data, # formerly, get_answer_functional_4(_data) key=itemgetter(tech) )

owing to the fact that data has already gone through the get_answer_functional_4 stage.

No really, is this a joke?

Those of you scratching your head and struggling to see how this is a workflow that makes problems easier to solve can relax. The steps described in the previous section are not ones that any programmer will ever have to do manually.

Simply by writing problems in a functional style using Higher Order functions, frameworks such as Apache Spark and PLINQ automate partitioning the data and merging the results at every stage.

In addition, the true benefit of this way of programming is revealed: each partition of data creates a standalone task that can be distributed to a worker node. If you have four cores, Spark can distribute the workload to all four of them greatly improving your code’s throughput.

Theory and Practice

The main barrier to using technologies like Spark are not the complex technical steps required to setup a multi-machine cluster. The real struggle is in knowing how to solve problems using Higher Order functions. Let me assure you, no matter how smart you are, reading a list of Higher Order functions won’t teach you how to use them.

The skill in being able to solve problems in a functional style comes from practising solving problems in a functional style. Even if you don’t see a case for using parallelisation libraries in the short term, I advise you to start solving problems using the Higher Order functions available in the language of your choice so that you’re prepared if that changes.

To this end I present you with a challenge. Here are two source code files for Python and C# that solve the same problem described earlier in both an Imperative and Functional style. Can you add a function that uses only chained Higher Order functions and finds the names of all programmers who have two skills greater than 75?

(Further reading – this blog post showing imperative Python code rewritten in a functional style is highly recommended)