Carpenters make tables and chairs, not hammers and saws

Ok, yes, I know it’s actually furniture makers who make tables and chairs but the title is long enough as it is. Just consider the point for a second though. Imagine the carpenter who has a problem with a broken saw or possibly a hammer that could have a better design for the type of nails they’re using. Do you think they crack open the welding torch or start on a new hammer mould? Of course not, they are carpenters – skilled at creating objects with wood. That is their business, what they have trained long and hard to be good at and how their time is most efficiently utilised.

It may seem obvious in this example that creating your own tools is folly but it happens every day in software development. No matter how noble the intentions are to save time and improve efficiency it creates problems. Problems that I’ve seen many a development manager ignore in favour of not spending money on saw doctors or blacksmiths.

Jack of all trades, master of none

You’ve heard this expression many times I expect and it’s especially true of business. Only the smallest companies do absolutely everything on their own without the help of 3rd party suppliers. Most businesses will be able to drill down to a concise description of what they are in business to do and it’s that description, that skill or talent that they compete on. Everything else is delegated to other companies who have the expertise and infrastructure to do so in a more cost effective manner.

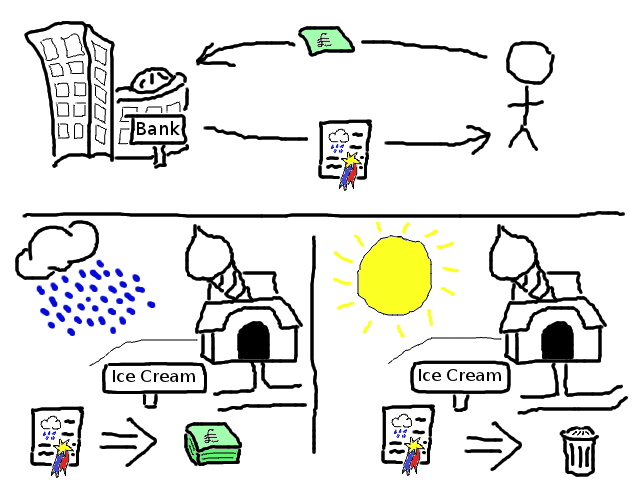

Imagine that you’re the owner of a small chain of ice-cream parlours. You’ve just created an amazing new flavour that’s a hit with the public, you have a close working relationship with local dairy farmers to get a low cost deal for milk, and you’ve secured perfect sea-front locations with friendly, inviting facilities. You have considered every aspect of your business and you’re ready to compete with anyone else when it comes to supplying the general public with ice-cream on a sunny day. And that’s just it, you can plan for every eventuality except rain.

Enter weather derivatives. The owner of the chain of ice-cream parlours can hedge against the risk of bad weather by buying weather derivatives that pay nothing if it’s sunny, but pay a lot if it’s unexpectedly inclement. This allows the owner to think about competing purely on selling ice-cream and ignore something that’s outside the control of the business. If the idea of weather derivatives strikes you as strange, focus on the idea that gave birth to this multi-billion dollar industry: successful companies like to compete on their strengths and don’t mind paying someone to make everything else go away.

The automation of the mundane

For as long as I can remember I’ve been fascinated by computer programming. My first taste was back in the 80s with BASIC on the Atari 800XL. Once you begin to see computers as a tool for automation, every task that has to be done more than a few times becomes a challenge; something that can be carried out by a program so it never has to trouble anyone again. As formal computer science education begins, programmers are trained to see these problems and design sound solutions to them.

For the voracious programmer, this process is ceaseless – everything can be improved upon, everything can be automated further. But as an employee of a large company, developers need to understand they are paid to write a particular type of software. Good software developers should always be masters of two disciplines: computer science and the business of the clients for whom they are writing software. For example, if the company a developer works for sells till machines, that developer should understand how sales assistants work and write software for till machines based on that understanding. They shouldn’t be writing software to handle build processes or libraries for logging error messages to a database.

When the development tools are all there at the fingertips of an able programmer however, the temptation is great to improve upon all elements of the development environment. This leads to the creation of software that isn’t destined to be sold by the business but rather used internally by developers or other colleagues. This is referred to as in-house (and sometimes custom or bespoke) software.

In-house development saves money

More often than not, it’s the company view that the sales department makes money whereas development costs money. Pressure is therefore put on development, most notably on the CTO and development managers, not to spend money unnecessarily. When enthusiastic and skilled problem solvers – keen to automate the mundane – spend a couple of months in a development team, they notice the bottlenecks and inefficiencies. Proactive developers will want to get ahead and raise their concerns with management but rather than doing so to cause trouble for all concerned, they do it with an offer of help. “The characters in this field are unicode rather than ascii so our database management tools can’t display them. I could write a small tool to allow us to display and maybe even edit them as well.”* If it looks like a common problem and the development cost isn’t too high it’s unlikely that their boss will turn them down.

*genuine example from the field

The developer gets to work on a new problem, their colleagues get to share in the solution and the manager gets a more efficient development team for no extra budgetary cost. It’s all win.

In-house development costs money

Except it’s not all win, not even close. When receiving the grand tour from the most senior development managers at my last two jobs, both took great delight in showing me in-house software tools that were organically created to solve previously troublesome problems. One was a tool to register and unregister COM DLLs, the other was a Python and PHP web-based issue management system. The teams were responsible for creating Market Risk software and real-time Financial Ticker Plant software respectively. This is completely at odds with my earlier assertion that businesses should compete on their strengths – a lesson that applies just as much to development teams as it does to companies.

So what are the problems that occur as a result of resorting to in-house development? Though it’s true that the company accountants will see savings from creating software internally rather than paying for 3rd party software, there are many costs that will not show up on the books.

- 1. Developers creating in-house software aren’t creating software that can be sold to customers.

This is probably the most obvious downside to in-house development. The Mythical Man-Month shows that when developing software there’s always a time penalty that cannot be reduced by adding more developers. Conversely, taking domain-specific developers away from creating saleable software and investing their time on a problem that another company has already solved will only delay the release date of future software.

- 2. In-house software increases the size of the code-base to be supported.

For most non-technical people, the assumption is that software developers are paid solely to develop software. This, however, is only a part of their responsibilities. As well as creating new software, developers spend the majority of their time maintaining and supporting existing software. Purchased 3rd party tools are built to be configurable to cope with changes to the way it’s used. In-house software has ongoing development costs as other changes take place. And unlike the ongoing support and development to the commercial software your company is selling, no money comes in for this.

- 3. No-one is an expert in all areas of software development.

One may argue that there is little difference between incurring salary costs for ongoing maintenance/development and licence costs for 3rd party software. But this is comparing the price of paying either a carpenter or a saw doctor to fix a saw: one is an expert, one is not. By sticking to the respective strengths of each development team, the most cost-effective use of time is spent by developers.

- 4. In-house software is from its inception low quality and made with arbitary assumptions.

As no customers will ever see in-house software, the quality of the final product in all aspects is reduced. There will likely be no installer, no documentation, poorly thought out or unprofessional UI design, and lack of wide-ranging exception and error handling. The best thing for such software is that it solves a small problem and, once finished, never needs to be touched again. However, the worst thing that could possibly happen is for (non-technical) senior management to view this software solution and fail to appreciate the difference between internal and shrink-wrapped software.

One of the worst cases of over elevation of in-house software I’ve seen was while working for a company with a multi-billion dollar annual turnover. A time and expenses reporting website was gradually rolled out over all business units across the globe and the ensuing chaos was tangible. There were countless bug-ridden fields, reports requiring unreachable states to be navigated before expenses could be approved, and dates and numbers failing to respect international formats. Poor layout and inadequate functionality were the most common features. By one development team failing to stick to the original remit of their business, and without the guidance of businessmen and women experienced with time and expenses reporting, this catastrophic state was allowed to occur.

- 5. Reliance on in-house software creates a hiring cul-de-sac.

This final attack on in-house development though not a financial or time penalty is, if left unchecked, the most dangerous to a development team. As a Windows developer I know how to use Visual Studio. There are many other key tools that will be used by developers to work effectively in a team. Knowing how to use them doesn’t happen by accident – this is down to teams choosing the best and most well known tools. The more developers rely on in-house software, the more alien the development process looks to outsiders coming in. The effect of this is two-fold: Firstly, hiring will become more difficult because savvy software developers will recognise the patchwork job holding the development process together and stay away. Secondly, developers who want to keep their skills relevant in today’s job market will recognise the damage their team’s in-house reliance is doing to their employability and possibly leave.

What should be done?

Some in-house development is ok. If the problem is small and static enough to be quick to implement and safe to discard the sourcecode, then by all means develop in-house. But if you’re concerned by any of the points I’ve enumerated then take a step back. It’s in the nature of software developers to solve problems and it’s sometimes hard to make the distinction between whether it’s a job related problem i.e. one that will make your company money, or one that will make things better. Most of the downsides to in-house development are not seen and thus not considered by non-technical managers. It’s up to developers to keep up-to-date with tools available on the market that can streamline the development environment and resolve their team’s issues. The case must be made to management that in-house development is not a long term solution for successful software development but a potentially dangerous burden for the future.