Addenda for Adopting Agile Development

Software Development is a strange profession. Coders are often promoted out of development in their thirties at the same time as new recruits are coming in who know different languages, tools and practices from those who graduated five years earlier. As a consequence, every aspect of the development environment is constantly up for reappraisal. Moving from one refactoring plug-in to another, say, is a pretty harmless change. Migrating source code versioning systems might be a little troublesome but will eventually quieten down. Changing the processes and methods of how software projects are planned, managed and developed though – that’s scary. And if it’s not scary, you probably haven’t understood the consequences fully.

Agile development, often used as a ‘best-practice’ buzzword, is an idea that has been around for a decade now. It was produced as a manifesto of principles leaving the implementation of these ideas open to different methodologies e.g. I have worked on projects using the Scrum method which adheres to the Agile development principles.

The selling points are convincing. Developers working in an Agile methodology will produce good code, produce it quickly, and deliver results that definitively solve their clients’ problems. But like any new way of doing something, there are new hurdles that must be considered if those promised benefits are to be realised.

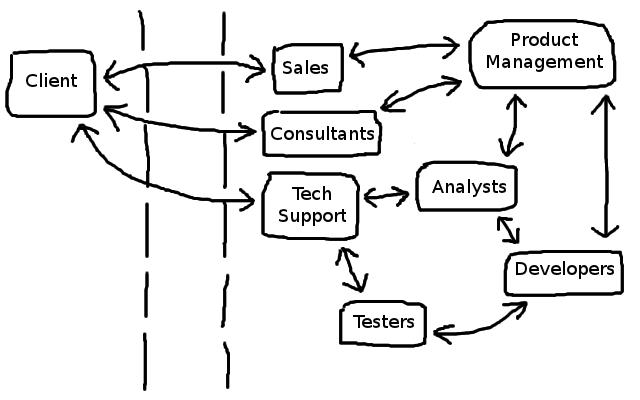

Old System

Here is a representative example of the main communication flows from a development viewpoint of a traditional large software house making bespoke, enterprise level software.

- Client – have a problem, want your company to write some software to solve it.

- Sales – sell software, convince client they have exactly the resources and experience needed to solve their problem

- Consultants – work with client’s technical people to install and configure software and ensure it’s working as they expect

- Tech Support – field support queries and investigate erroneous software behaviour

- Product Management – decide what software to create, decide what enhancements and bugfixes to provide, decide on how to manage available development resources and produce schedules for software releases

- Analysts – have the technical knowledge needed to investigate problems with the software but also have the business knowledge to understand what the software should be doing

- Developers – create and maintain software

- Testers – responsible for testing newly developed software thoroughly, finding bugs and reporting them back to development.

After a successful agreement between the client and the sales team, software is commissioned and, with some variation depending on the practices of the software house involved, the following process starts where certain groups collaborate to produce the next stage of the software development cycle from initial contract to accepted, delivered software.

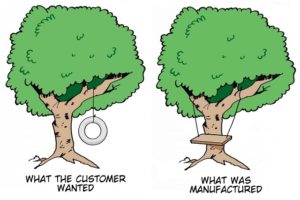

The main thing to notice about this workflow is that all the tasks are done in one big cycle, one after the other. One party does as much work as it’s possible to do before moving the task on to the next. Two problems are endemic of this system. Firstly, estimates can be wildly inaccurate because the complete development cost will always be held up by unforeseen difficulties i.e. ones which by their very nature cannot be estimated. Secondly, between the long trail of Chinese Whispers from the last moment the client defines their requirements to when the finished software is handed to them, all kinds of misunderstandings could have occurred. It’s unlikely that the solution solves the client’s problem in the way they expected.

Another thing to notice about this system is how far removed the clients and development are from each other. This is not a design implication that has occurred by chance but rather something that both the developers and the software house are keen to ensure. My first interaction with computer scientists was as a high school student visiting my local university. Two men greeted our group both sporting unkempt beards and wearing sandals with socks. Things have gotten a lot better in the prevailing years but there will always be an element of the socially awkward about many developers. This is something that a slick, professional software house is keen to hide (I’ve worked for two Fortune 500 companies and both times our development teams were housed in remote silos well away from the main headquarters).

Anyone who’s had the misfortune of dealing with an unhappy, possibly outright angry, client knows how stressful and unpleasant that can be. Developers are therefore likewise quite happy to be placed in their silo, free to concentrate on delivering software to specifications given to them according to predictable timescales rather than tirades of angry swearing.

Chinese whispers via specifications

With this high degree of separation between development and clients how on earth does working software that genuinely solves problems ever get produced? Ideally the developers will have a clear understanding of their clients’ business so before any project even starts they know roughly what is required. There may be a few members of the development team who “wear two hats” and can act as an analyst too – a handy reference for the rest of the team. But if there is no specialist knowledge available all a developer can do is fall back on the specification.

A project may be badly planned and poorly defined from the beginning. The developer charged with writing software for such a project can look at a poor functional or technical specification and alert their team leader to take it up with the analysts or product management. If that goes nowhere, all the developer can do is implement the specification as precisely as possible. Regardless of how inappropriate the final software solution is, when months later the fallout occurs the developer can point to the specification and say they did as they were instructed. The latency in moving the process from inception to conclusion means that no-one wants to be blamed for eventual failure. Specifications become safety contracts to work against rather than tools to producing working software for a client.

Agile Manifesto

Enter the Agile Manifesto. Twelve principles that aim to break down the lengthy cycle of specifications, development and acceptance testing to get rid of the problems of under-estimating timescales and delivering bad software. A detailed explanation of these principles is outside the remit of this article but I’ll instead discuss how implementing an Agile methodology affects the more traditional development workflow described above.

The basic Agile theme is two-fold, rather than one big cycle that results in a software deliverable there are several much smaller cycles. Also, rather than expecting the client to know exactly what they want to begin with, their problem is understood in much looser terms and can be changed between the small development cycles. Small development iterations are conducted that allow the client to see how the solution evolves as it is developed. The initial offerings may be almost completely functionally devoid but allow the client to understand the vision of how things will work. Smaller development cycles ensure smaller workloads with more predictable timescales. Allowing feedback from the client along the way means they’ll be happy with the finished product – even if it’s something completely different to what they first envisioned.

“No more specs? Great!”

This line was uttered by an excited colleague of mine while learning about the Agile methodology we were moving toward. Such steps should be approached carefully though. By hand picking just the bits that you like from a new way of doing things rather than soberly implementing them as instructed, it’s unlikely to work as planned.

But without exhaustive specifications it’s a valid question to ask what happens now? How does a development manager who wants to move to Agile development do so? Short answer: they don’t. At least, not on their own they don’t. To make a programming analogy, you can’t just change an API you implement to move from processing arrays of objects to processing individual objects. You have to get the approval of all those who depend on your implementation.

Changing a refactoring plug-in will affect the developers who choose to use such tools. Properly implementing an Agile development methodology affects the day to day working practices of not just everyone within development but also everyone who works with development. If it doesn’t then the smaller software cycles are not being distributed all the way back to the client and thus miss out on the crucial feedback required to be Agile. It’s therefore not enough for the Development Lead or even CIO to decide, “We’re going Agile.” Everyone, including the software house’s clients, must be involved in the decision.

Let’s examine some of the Agile principles to highlight this point.

- 4. Business people and developers must work together daily throughout the project.

Rather than product management and analysts providing specifications and waiting until development have finished producing software, daily interaction provides constant status updates and opportunities for guidance on how development should proceed.

- 1. Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software.

- 2. Welcome changing requirements, even late in development. Agile processes harness change for the customer’s competitive advantage.

All well and good so far. But regardless of the size of the software deliverable from development or the number of alterations and extra requirements from the client, there is some fixed time penalty passing these from team to team. Expecting more iterations on top of the prospect of daily meetings is at odds with the following principle:

- 3. Deliver working software frequently, from a couple of weeks to a couple of months, with a preference to the shorter timescale.

It’s hard to see how the protective layer 3-tiers deep between development and clients can remain if we are to adhere to the Agile principles. Agile development will increasingly see developers having to step-up socially to become better and more professional communicators. There is more than just the pressure on timescales though as developers will also face the loss of specifications as their safety contract. Developers will as always be required to use their judgement to decide how best to solve the problem they have been given. Without a specification as a reference they must gain a better understanding of the client’s business needs to make informed coding choices.

Software Planning and Delivery Solved?

Is Agile development the panacea for producing good software? No, as has always been the case, there are no silver bullets for software engineering. Agile development methodologies properly implemented, however, make developers more instantaneously accountable, better communicators and produces software on more predictable timescales that is more likely to match their clients’ desires.

As much as I’m an a convert and advocate of Agile development, the cynic in me cannot ignore a detail that is hidden away in one of the principles:

- 5. Build projects around motivated individuals. Give them the environment and support they need, and trust them to get the job done.

It may well be the case that a software house does not have enough money or interesting work to have such individuals. If they did they may well have realised that motivated developers often work hard enough to pull success out of the bag regardless of the bureaucratic constraints put upon them by a bad software development process.