Counting Like A Computer

The journey of learning about Computer Science will start by revisiting a simple lesson first encountered by most as a toddler: how to count. Indeed, it’s such an easy skill it’s hard to remember a time when you didn’t know how to do it. But one of the commonly known facts about computers is that everything is done in ones and zeros ie. binary. Just what does that mean though and how is any of this relevant to humans? Well, to understand how a computer works, you have to be able to work things out like they do. The first step is learning to count like them.

Let’s start simple by revisiting how we count. Here are the ten single digit numbers.

\[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9\]

The rules are so straightforward that given any number, you’d know how to start counting from there upwards. Consider this example in the tens of millions. The number is split up into Units, Tens, Hundreds, Thousands, Tens of Thousands, Hundreds of Thousands, Millions and Tens of Millions, as appropriate.

\[21,684,997\]

|

Start at the Units column and move your way up the numbers in order from 0 to 9. When you add one to 9, loop back to 0 and add one to the next column along i.e. the Tens column. Keep on applying that rule and move up through the columns e.g. adding one to ninety-nine sees us loop back to 0 in the Units column, loop back to 0 in the Tens column, and repeat the same pattern in the Hundreds column. Elementary!

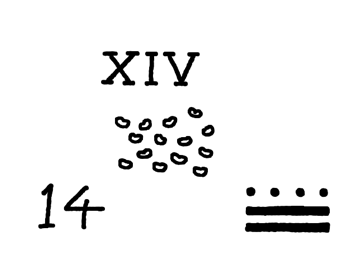

It’s important to understand, however, that the digits we write out in a line are just a way of describing a quantity according to the rules of our number system. The symbols 1, 2, and 3, or indeed 123 only mean something to us because we implicity and simultaneously attach a meaning to the digits both individually (6 is two more than 4) and collectively (despite being made up of smaller individual digits, 103 is larger than 89). Like us, earlier civilisations used many different symbols and systems for describing the concept of a number. Consider the following depictions of the number fourteen:

The digits 1 and 4 placed side by side only mean something to us because we understand the rules of our number system. To the Romans, X meant ten, V meant five, I meant one, and XIV (“ten” and, “one before five”) meant fourteen. Likewise the Mayan system had a horizontal bar which meant five, and dots which meant one. Two bars and four dots as arranged above also represents fourteen.

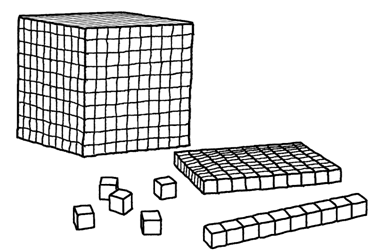

Perhaps, like me in your early years of primary school you remember using shapes like these in mathematics lessons.

These were used to simplify the process of how you described numbers beyond those represented with just a single digit. Elementary arithmetic was made possible by considering a number as the sum of a number of hundreds, tens and units.

|

H

|

T

|

U

|

|

2

|

7

|

4

|

\[2 7 4 = 2 \times 100 + 7 \times 10 + 4 \times 1\]

Two-hundred and seventy-four, denoted in our number system as 274, can be broken down in into two hundreds, seven tens and four units.

You are hopefully feeling confident in your well worn skills of counting so I’ll move on. Of the two number systems described above – Roman and Mayan – consider for a moment which is the most similar to our own?

Despite sharing a similar alphabet, the rules regarding counting in Roman numerals are completely different to ours because the Romans lacked the concept of zero. We can only move easily from one column to the next when counting upwards because of our 0 digit. The lack of a zero symbol in Roman numerals mean that to represent larger numbers, we need more and more symbols e.g. X is 10, C is 100 and M is 1,000. The Mayan’s number system, though pictoral, shares our concept of zero and is very similar to our own in that it follows similar rules. They start counting at zero, denoted by this symbol.

They move from a single dot representing one up to the following.

This symbol with three horizontal bars and four dots represents the number nineteen. Adding one to this symbol is not represented by four horizontal bars, but rather a flip back to the zero symbol and adding one to the next row. This image is the Mayan representation of twenty.

The symbols are different but otherwise the way counting works is very similar. What is the big difference you notice in moving from one row to the next compared to our number system? It’s that the Mayans move after twenty digits, whereas we only use ten.

Anthropologists throughout the ages have encountered ancient and modern cultures alike who all have number systems that work in the same way: enumerate all your symbols from zero to your largest, then go back to zero and add one to the next column or row. The symbols used are always different but that’s not particularly important – we can think about that as variations in handwriting. The crucial difference and the most important question that a mathematician will ask about a number system is, “What base is it?” Quite simply, this means how many different symbols are there. Our number system has ten distinct digits from 0 to 9 inclusive and thus we have a base-ten number system, also known as decimal.

The Mayans used bars and dots to abbreviate how their symbols were transcribed but we still count the symbols from zero to nineteen as distinct. Thus, the Mayan number system was base-twenty. Now that you’ve been told about the importance the base of a number system, we’ll refine your understanding of counting so that you can count in not just decimal but all number systems.

Positions of power

Consider the example of two-hundred and seventy-four we saw earlier in this chapter. We broke this down into the sum of three simple terms, \(2 \times 100\), \(7 \times 10\) and \(4 \times 1\). But really, the hundreds, tens and units are something that your primary school teachers made you memorise instead of explaining how to derive them yourself. The factor of each of column i.e. what the value is multiplied by, is the base raised to the power of that column.

If you haven’t heard the term power, or raising a number to a power, it’s quite straightforward.

Ten to the power of two, written as \(10^{2}\), means \(10 \times 10\), which is \(100\). Ten to the power of three, or \(10^{3}\), is \(10 \times 10 \times 10\) which is \(1,000\). Indeed, in the decimal numbering system, raising ten to a particular power is quite easy to calculate, it’s simply the number of zeros after a one. So \(10^{5}\) is \(100,000\) and \(10^{0}\) is 1.

By numbering the columns from zero upwards, we can calculate the value of each columns factor as the base of the number system raised to the number of that column. Two-hundred and seventy-four becomes \(2 \times 10^{2} + 7 \times 10^{1} + 4 \times 10^{0}\).

Any number represented in one number system can be recreated in another following exactly these rules. How do we write two-hundred and seventy-four in the Mayan system then? We’ll rush into it and see how we go.

First up we need to translate our symbols from decimal digits into Mayan scriptures. The 2 is represented by two dots, 7 by two dots on one bar and 4 by four dots. The whole thing looks like this:

The problem we haven’t thought about, however, is that the Mayan base is twenty. The symbol we’ve just written down is \(2 × 20^{2} +\) \(7 \times 20^{1} +\) \(4 \times 20^{0}\). Whereas the column factors in our decimal number system are 1, 10 and 100, in the Mayan number system they are 1*, 20 and 400 (twenty times twenty is four hundred). Even though we see two dots in the highest row, the value of that is eight-hundred i.e. two multiplied by four-hundred. The two dots and one bar in the next row have the value of seven multiplied by twenty, which is one-hundred and forty. And finally the last row containing four dots, similarly to decimal, is simply four. Adding the three terms together we can see that what we wrote down isn’t 274, but rather 944! Here is what 274 in Mayan actually looks like.

*Without going into the detail of explaining the underlying mathematics, any number (in this case twenty) raised to the power of zero, is one.

This depiction is represented by the Mayan symbols for thirteen (two bars and three dots) followed by fourteen (two bars and four dots). You can verify yourself that:

\[13 \times 20^{1} + 14 \times 20^{0} =\]

\[(13 \times 20) + (14 \times 1) =\]

\[260 + 14 =\]

\[274\]

Why have different bases?

Did you ever stop to think why we have only ten digits when the Latin script alphabet has twenty-six letters? Digits. A term also used to refer to our fingers and thumbs, of which we largely have ten. This is no coincidence. Our current numbering system chose to use ten digits because it simplifies counting on our ten fingers. Essentially, the way our bodies evolved drove out the choice to use ten as the base for our number system.

Computers on the other hand, at their most fundamental, basic level, do not understand our base-ten number system. They transmit information internally using subtly varying electrical signals. The analogue variations in voltage travelling through the countless electronic circuits within our computers are hard to gauge – or even transmit – accurately and reliably. As a consequence of needing to allow for greater margins of error, we only consider two states, namely, a pulse between roughly 0 and 0.5 volts, and another between roughly 2.5 and 5 volts (depending on the hardware). These refer to on or off; 1 or 0; the base-two numbering system that is the root of all calculations performed by computers: binary.

There are reasons other than just fluctuating voltage signals that make a base-two number system advantageous to computers – but we’ll come to those later. It’s worth mentioning, however, that unlike trends in technology which change and evolve with time, the fact that the lowest level of computation performed by electronic devices is done using base-two will always be the case. Already you are learning information that will not go obsolete.

Next time we’ll explore binary further including how to add and count in binary; convert between binary and decimal; and demonstrate exactly what is going on at the tiniest, most basic level inside your electronic devices.